5/25/14 UPDATE! Based on people’s comments and my own further ruminations, I somewhat revised and substantially extended the article described and linked to in this post. You can find the revised version here.

Have you ever noticed that sometimes mindfulness practitioners seem sort of stiff or zombie-like in life? I went through a long period of that. What cured me was my encounter with Zen. Zen puts a big emphasis on acting, speaking, and thinking from a place of dynamic spontaneity. Zen spontaneity might be thought of as the motor analog of what I call flow).

Recently I’ve been thinking that perhaps practice should involve explicitly training of one’s motor circuits as well as training of one’s sensory circuits. In Buddhism, action (Sanskrit karma) is traditionally analyzed into three categories: body (kāya) action, speech (vāk) action, and thought (citta) action. I find it interesting that thought can be viewed as both a sensory experience (vijñāna) and a volition action (karma). When you think about it, it makes sense. On one hand, we see mental images and hear mental talk (sensory perceptions). On the other hand we visualize situations and mentally discuss them (intentional actions). Although we tend to think of the word “motor” as relating to the control of muscles, we should perhaps generalize that adjective to include the aspects of thought that are under voluntary control. I suspect that when neuroscience is finally able to map human thought circuitry, it will contain both sensory elements and motor elements.

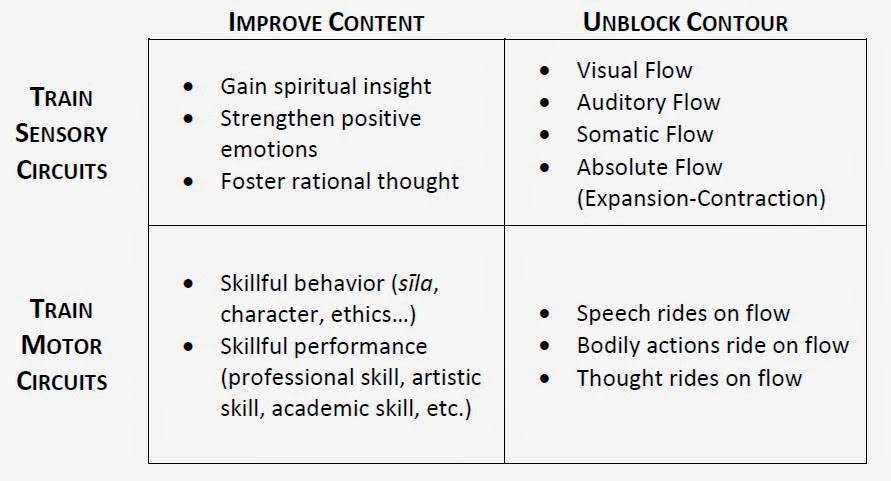

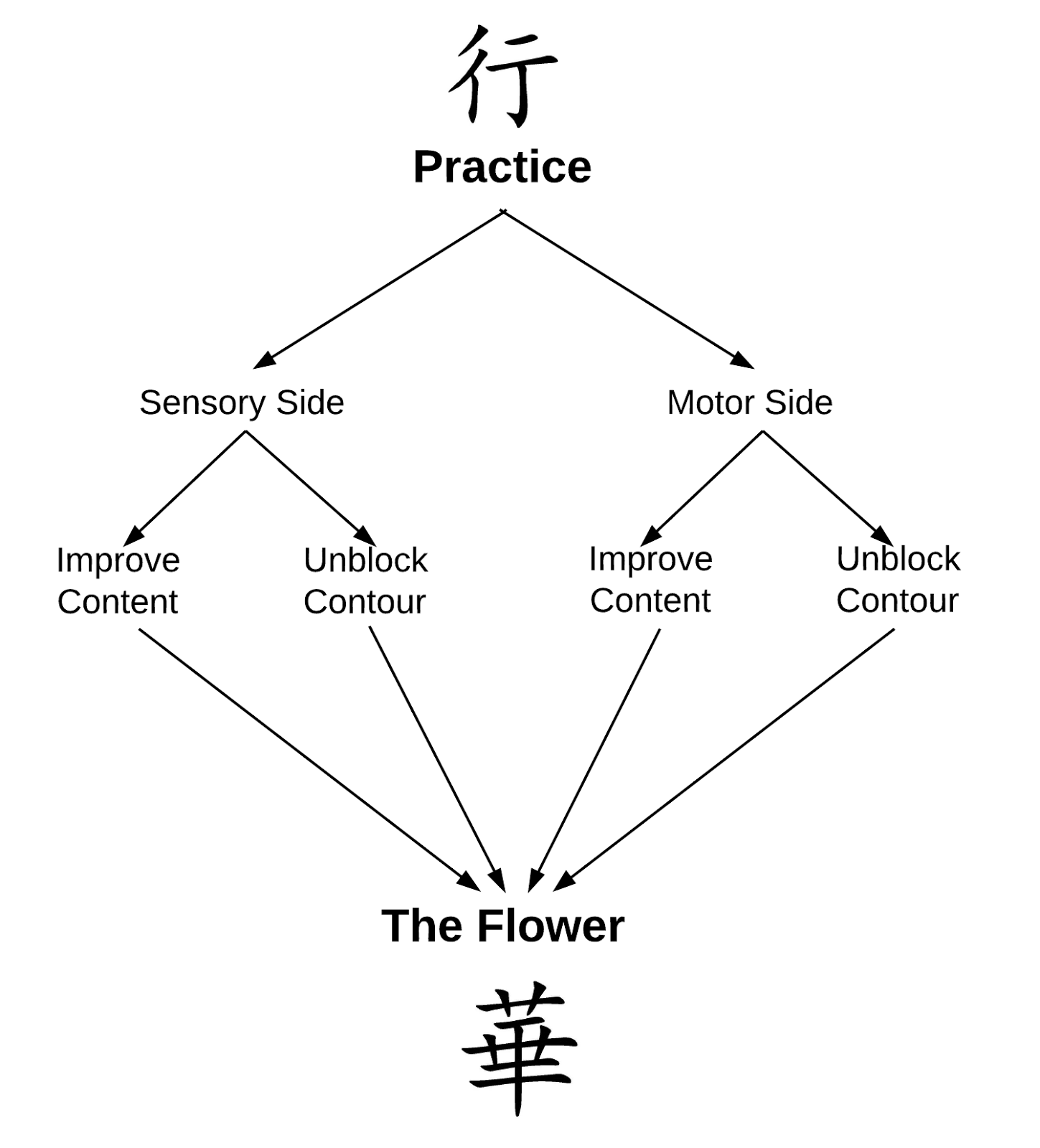

Big picture wise, we could analyze psycho-spiritual practice in terms of two binary contrasts:

Sensory Training vs Motor Training Improving Content vs Unblocking Contour

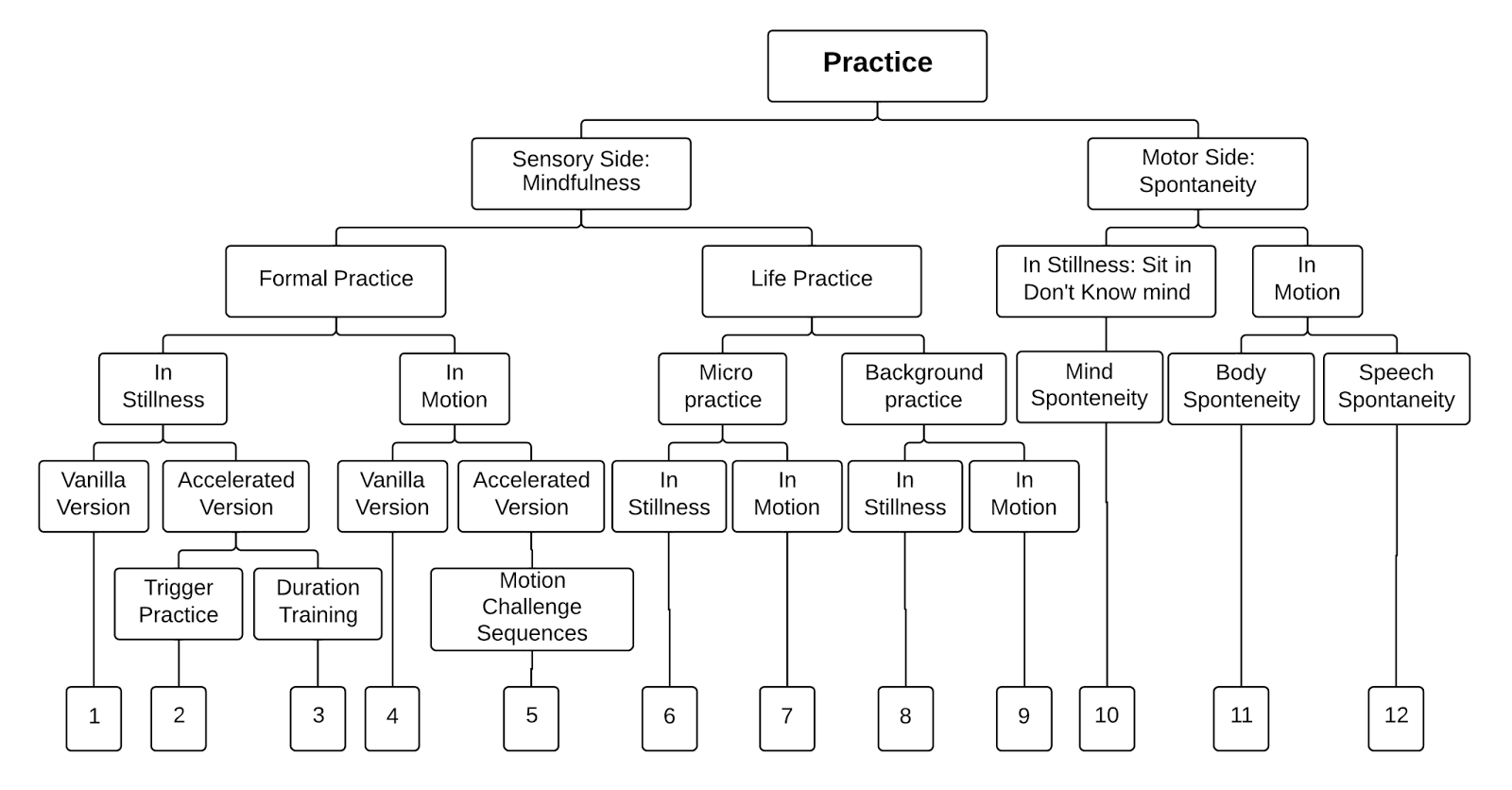

Putting all these notions together, we can construct a truly comprehensive outline of practice.

By “The Flower” I mean the flower of humanity, the full human flourishing that comes about when one’s substance conforms to the flow of nature and one’s behavior conforms to the cannons of humanity.

I. Sensory Side: Mindfulness

A. Formal Practice

. Attention: All attention is on the technique.

. Duration: Practice period lasts at least 10 minutes.

1. In Stillness

Vanilla version

. Default situation: Sitting

. Other common situations:

a. Standing

b. Lying down

c. Holding a yoga posture

Accelerated versions

. Same as vanilla version but in addition systematically expose yourself to a wide range of triggersor work to extend the duration of your sessions.

2. In Motion

Vanilla version

. Default situation: walking

. Other common situations:

a. Chanting

b. Eating

c. Exercise

d. Simple chores

Accelerated versions

. For a given technique, create a challenge sequence. The goal is to eventually be able to “go deep” with that technique even while doing a complex activity.

B. Life Practice

1. Micro Practice

. Attention: All attention on technique.

. Duration: Under 10 minutes, i.e., you give yourself “microhits” during the day; 30 seconds here, 3 minutes there (emphasis must be quality over quantity; if need be use spoken labels to assure this).

2. Background Practice

. Attention: Not necessarily much attention on the technique (it’s sort of running on its own in the background).

. Duration: Any length of time (even most of the day).

II. Motor Side: Spontaneity

A. In Stillness: Sitting in Don’t Know mind leads to ability to “think without thinking”, i.e., wisdom thoughts well up spontaneously once you have worked through the drive to think. (This is part, but not all, of what’s called kōan practice.)

B. In Motion:

1. Body spontaneity: In Zen three words beginning with S foster this.

. Samu– Zen work: Totally give yourself to the pure doing of the task. (The flow of expansion and contraction animate your limbs.)

. Sahō– Ritualism: Once you master the elaborate forms, you can fall into the ritual—literally! No need to think; action just happens the way a raindrop just falls.

. Sanzen– Interviews with the Roshi during which he/she demonstrates/transmits effortless doing.

2. Speech spontaneity: Throw caution to the wind, start flapping your tongue and moving your lips with faith that coherent speech will self organize sooner or later.

III. Further Notes

A. Notice that any of the three approaches (formal practice, micropractice, background practice) can be implemented in either of 2 basic situations (in stillness or in motion).

B. Here’s a general suggestion for developing the spontaneity dimension of practice: A period of practice (one sit, a whole retreat), may leave you perceptually and/or conceptually disoriented. Instead of trying to reorient/reground yourself, do two things:

. Have equanimity with the disorientation.

. Start functioning despite it, i.e., act and speak from the state of Don’t Know. You may be a little awkward at first but that passes.

C. The above breakdown of practice yields 12 distinguishable practice situations. Paraphrasing Bill of Big Book fame: Seldom have we seen someone fail who has implemented all 12 of these.